Before continuing with my tale, I want to emphasize that the Dharma was remarkably widespread throughout the snowy land of Tibet. It so permeated our society that even small children didn’t have to deliberately study prayers such as the supplication to the Lotus-Born master. They would learn how to chant it just by growing up in this Buddhist environment and hearing it over and over.

Children’s games reflected this atmosphere and we often played at building monasteries. Groups of us kids would pile up mud and stones, under my supervision, and we managed to make some small “temples” in which we would play “lama.” Sometimes these games went on from early morning until sunset.

Aside from the hermits and vast assemblage of monks and nuns living in the big monasteries, practitioners often stayed together in large encampments, such as the group surrounding Shakya Shri. For instance, the seventh Karmapa never stayed long in one place but moved from one camp to another throughout Tibet. Any offerings he received he would pass along on the spot to the local monasteries.

The seventh Karmapa’s close entourage consisted of at least one thousand monks, who followed along wherever the Karmapa went. The monks and attendants with their horses and yaks were so numerous that not everybody could fit in one place. So they staggered their movements in groups of one hundred, camping at seven or more different places a day’s travel apart, staying a day in each place.

People camped in tiny meditation tents with a single pole, just big enough to sit in. The whole monastic community would stay in such tents, though the master’s tent was typically larger. They were all required to keep the Kagyu tradition of four practice sessions a day, even while traveling. At a designated time, a bell would be rung and they would eat their meal together.

As soon as the meal was completed, according to the tradition, they would recite the Kangyur, the Buddhist canon in one hundred large volumes. As they traveled along, walking in a line across a vast plain, younger monks would distribute separate pages to each of the hundred monks, collecting the pages as they finished. All together they could easily complete all one hundred volumes by the time they reached the next mountain range, each monk reciting just two or three pages from each volume. The whole encampment was so large that, when everyone was together, the monks could recite the whole Kangyur in just an hour. The heap of their used tea leaves was often as tall as a man.

The Karmapa’s caravan was known as “the great encampment that adorns the world,” one of countless examples illustrating how deeply the Dharma was woven into our very existence.

From Blazing Splendor, the memoirs of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche

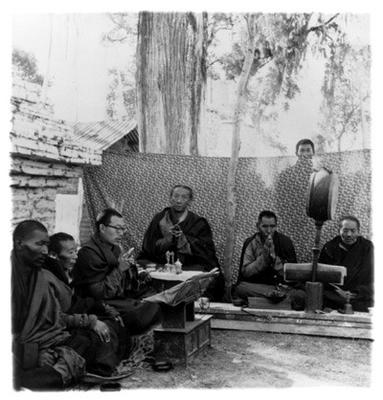

Earlier in this weblog it was brought up that Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche may have been the first Tibetan Lama to visit Southeast Asia. At that time I asked for some photos and Anne sent this and two other photos. The large Chinese monk to Rinpoche's right is Khoo Poh Kong, and to his left is the British monk Lodro Thaye.

Earlier in this weblog it was brought up that Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche may have been the first Tibetan Lama to visit Southeast Asia. At that time I asked for some photos and Anne sent this and two other photos. The large Chinese monk to Rinpoche's right is Khoo Poh Kong, and to his left is the British monk Lodro Thaye.